| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The John Henry legend tells of the strong black worker who won a contest against a steam-powered drill during the railroad-building era of the late 19th century.

According to the legend John Henry was a steel driver. Using just a hammer and his own strong arms, he drove a steel bit deeper into the rock than the steam drill could do in the same period of time. He died of exhaustion soon afterwards, his heroic feat costing him his life. Those are the elements on which the legend is based, though there are many variations.

Generations of folklorists and historians have tried to prove John Henry really existed and to place the alleged contest. Early research pointed to the Big Bend Tunnel in Summers County, West Virginia, as the site of John Henry’s deed.

In the 1920s a rivalry developed between two professors researching John Henry – Louis Chappell of West Virginia University (shown here) and Guy Johnson of the University of North Carolina. They never agreed on the details, but both placed the story in West Virginia. Others claim that John Henry beat the steam drill in Alabama or Virginia or Jamaica.

The story of John Henry is part of the larger story of the growth of America and the expansion of the nation’s railroad system. After the Civil War there was renewed interest in pushing rail lines to the west.

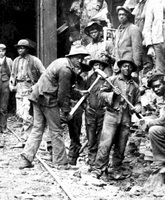

In 1870 the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company began to build a new line across southern West Virginia, mostly following the Greenbrier, New, and Kanawha Rivers to reach the Ohio River at Huntington. The line was completed in January 1873, when the eastbound (pictured) and westbound construction crews met at Fayette Station on the New River.

If John Henry did exist as a black man in the 1870s, probably he was a former slave. Such “freedmen” joined a large labor force that migrated from the South to work in the North and Midwest.

Over 5,000 African-Americans worked as laborers for the C&O and its contractors during 1871. They labored 10 hours or more for less than a dollar a day. They cleared the way, hauled rock and debris, prepared the road bed, built tunnels and bridges, and laid track. The crews included convicts leased from prisons and some think John Henry may have been among those men.

Click the thumbnail above to hear a 1937 labor crew sing a work song.

When construction engineers reached Big Bend Mountain in Summers County in 1870 they had a decision to make. Would they lay 13 miles of track following the Greenbrier River around the mountain or bore a mile-long tunnel through it? Calculating that the long-term savings in mileage would exceed the cost of the tunnel, they decided to go through the mountain. They would build the Great Bend Tunnel, better known as Big Bend, the longest tunnel in the United States at the time. It took three years to build and was completed in 1872. The route of the tunnel through the mountain is illustrated by the blue line on the map below.

View Big Bend Tunnel in a larger map

John Henry was a steel driver whose job was to make holes for the explosives used to blast away rock at the heading of the tunnel. To do this he used a heavy, long-handled hammer to drive a steel drill into the rock face. When the drill reached the proper depth it was removed, the hole packed with explosives and the rock blasted free. The process then started over again. Every driver had a partner called a turner or shaker who held the drill and turned it after each blow of the hammer. These two-man teams were highly coordinated.

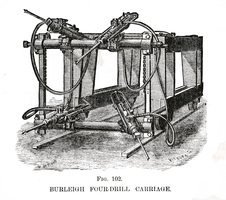

As hard as the shakers and steel drivers worked, their progress was slow. Addressing this problem, rock drilling technology improved. Between 1850 and 1875, American inventors patented more than 100 mechanical drills. The Burleigh compressed air steam drill was among them, and possibly was the drill confronted by John Henry.

Steam drills gained favor as they became more reliable and as they gained portability and the flexibility to drill in multiple directions and positions. Manufacturers marketed their contraptions as savers of time and money with demonstrations on the job site.

Key verses of the song describe the great battle between John Henry and the steam drill. Humbled by the mountain before him, “he laid down his hammer and he cried.” But he did not bow to the steam drill. While admitting that “a man ain’t nothing but a man,” he vowed to outdo the machine or die trying. “Before I let that steam drill beat me down, I’ll die with a hammer in my hand, Lord, Lord.” But ultimately, “John Henry drove 14 feet of steel, the steam drill only drove nine.” The effort cost him his life.

No doubt the large family of songs about John Henry have been the most important conduit of his story. The earliest mentions of John Henry occurred in work songs sung by coal miners and railroad workers in the late 19th century. In 1911 folklorist Josiah Combs obtained a complete version of the song in eastern Kentucky that specifically mentioned the Big Bend Tunnel on the C&O Railroad. Folklorists at the Library of Congress have called it the most researched folk song in the United States and possibly the world. Fiddlin’ John Carson (pictured) performed one of the earliest known recordings of a John Henry song in 1924. There are hundreds of recordings in every conceivable musical genre.

Click the image to hear Fiddlin’ John Carson play John Henry.

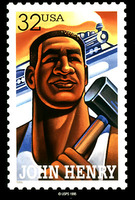

John Henry is one of the world’s most enduring folk heroes. His story has inspired songs, books, films, artwork, festivals, and theatrical productions. In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a John Henry postage stamp at a special ceremony in Talcott, near the Big Bend Tunnel.

John Henry is the story of man’s triumph over machine and the nobility of the human spirit. At least three essential themes within the legend – the value of work, the significance of race, and the social cost of technological innovation – may each be considered the definitive element of the story, and each may be interpreted differently. Most people can relate to at least one of these story elements and find their own connection with the legendary hero.

The material for this exhibit was drawn from a Humanities Council traveling exhibit, John Henry: The Steel Drivin’ Man. The original traveling exhibit is on permanent loan to the Frank and Jane Gabor West Virginia Folklife Center at Fairmont State University.