| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

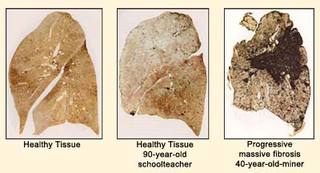

Coal miner’s pneumoconiosis, or black lung disease, results from the inhalation of coal dust. Human anatomy filters out the larger dust particles, but the smallest manage to reach the alveoli, or air sacs, of the lungs. These air sacs exchange gases with the blood. Over time, inhaling substantial quantities of coal particles causes the air sacs to lose elasticity and become weaker, contributing to emphysema. Deposits of dust-containing blood cells become permanently lodged in the lungs, restricting airflow and producing chronic bronchitis. A miner in the early stages of this disease may experience occasional shortness of breath and coughing that eventually increases in frequency. Later symptoms include wheezing and pressure or tightness in the chest. Because it curtails oxygenation of the blood, pneumoconiosis may result in high blood pressure, enlarged heart, heart attack, or acute pneumonia.

Some early 19th-century physicians and critics of industrialization noted the symptoms of what was then referred to as ‘‘miner’s asthma.’’ The disease increased dramatically with 20th-century mine mechanization, which increased the level of dust in mining. Unfortunately, x-ray techniques failed to provide an efficient tool for diagnosing the medical effects of coal dust in the lungs. Black lung was denied as a real disease until established by crusading doctors after midcentury. A 1954 scholarly article by West Virginia physician Joseph E. Martin Jr. insisted that black lung was indeed a progressive, terminal disease associated with exposure to coal dust. By the 1960s, a small group of doctors, especially Donald Rasmussen, conducted research, pioneered alternative forms of diagnosis, and offered mounting medical evidence of black lung as an occupational disease. Rasmussen and other activist physicians such as I. E. Buff and Hawey A. Wells Jr. joined with the rank-and-file miners of the Black Lung Association to educate miners, the public, and politicians about the disease. Legislation declaring black lung a compensable injury passed the West Virginia legislature in 1969 and became federal law later the same year.

In 2017, after years of decreasing black lung cases, clinics in West Virginia and surrounding states reported a surge in cases of “complicated” black lung, or progressive massive fibrosis (PMF), the disease’s most advanced form. The more recent cases of PMF include many miners at a younger age and with less than 20 years of mining. The likely cause of the epidemic is longer work shifts for miners and the mining of thinner coal seams. Mining machines cut rock with the coal in these seams, and the resulting dust contains silica, which is far more toxic than coal dust. The surge in diagnoses may also be related to the job market; miners who avoided the voluntary black lung testing while working are now visiting clinics to apply for black lung compensation. Additionally, in 2016 the Mining Safety and Health Administration’s Respirable Dust Rule lowered mine dust concentration limits.

By the early 2020s, PMF was being found in rates not seen in Central Appalachia since the early 1970s. Between 2019 and mid 2023, nearly 30 percent of all Americans diagnosed with PMF were from West Virginia. On June 30, 2023, the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration proposed more stringent rules that would reduce exposure to silica dust in mines. President Biden revealed the new rules on April 23, 2024, limiting by half the allowable concentrations of silica dust in a mine and requiring companies to monitor these levels actively.

Written by Paul H. Rakes

Smith, Barbara E. Digging our Own Graves: Coal Miners and the Struggle over Black Lung Disease. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987.

Howard Berkes and Adelina Lucianese. Black Lung Study Finds Biggest Cluster Ever Of Fatal Coal Miners' Disease. National Public Radio, February 6, 2018. .

U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration. US Department of Labor Announces Proposed Rule to Reduce Silica Dust Exposure, Better Protect Miners’ Health. U.S. Department of Labor. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, June 30, 2023.