| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

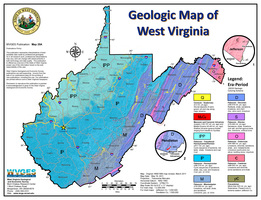

An acquaintance with geology is necessary for a full appreciation of West Virginia’s settlement history, past and present land use, and economic and cultural development. Different areas exhibit different economic activities and cultural styles. Historically, many of those differences have been influenced, directly or indirectly, by geology. While all of West Virginia lies within what is considered the Appalachian region, the state is diverse, having several distinct physiographic areas, each with its own characteristics.

With few exceptions, the consolidated bedrock lying at and near the surface throughout West Virginia is sedimentary rock initially deposited as soft sediments during the Paleozoic Era, a geologic period that lasted from more than 570 million to about 230 million to 240 million years ago. Throughout that unimaginably long time, present West Virginia (and indeed, the entire Appalachian area, from New York to Alabama) was covered by or lay close to a shallow sea. The mountains of Old Appalachia, ancestors to our present mountains, lay to the east, and erosion of those highlands brought sediment into the shallow sea. This sea floor or Appalachian geosyncline intermittently subsided, continuing to accept sediment over thousands of centuries.

Intermittent basin subsidence as well as uplift of the adjacent Old Appalachian Mountains were caused by collisions and separations of the North American continental plate with the European-African plate. Cycles of deposition and subsidence, along with periodic climate changes, resulted in a diversity of sediments which became limestones, shales, siltstones, sandstones, and coals. These rock types formed in such environments as shallow seas, beaches and deltas, and coastal plains with rivers, swamps, bays, and lagoons. The mineral resources associated with the rocks (coal, oil, gas, salt, limestone, glass sand) have been important to the state’s economy, historically and at present, and vary from one part of the state to another.

The close of the Paleozoic Era was marked by continental plate collision which compressed flat-lying strata and pushed them from east to west into uplifted folds, a great mountain-building event known as the Appalachian Orogeny. The large sedimentary basin that had existed in varying forms for more than 330 million years ceased to exist. Since then, the area has been shaped and characterized by weathering and erosion. The mountains have been eroded down to a fairly level plain, uplifted again about 30 million to 50 million years ago, and then eroded again to form our present landscape.

A final phase of some sediment deposition occurred during the Great Ice Age, or Pleistocene Epoch. During that most recent period of glacier advances into the present United States, lasting from about 1,000,000 to about 10,000 years ago, the glaciers never extended quite as far south as present West Virginia, but they nevertheless exerted still-present influences on the state’s geology, landscape, and flora and fauna. The valley of the prehistoric Teays River, represented today by a broad, flat valley extending essentially from Charleston to Huntington (and across southern Ohio), is filled with lake sediments resulting from damming of the ancient river by glaciers at a point near Chillicothe, Ohio. The Ohio River, which did not exist prior to the Great Ice Age, was created by blockage and diversion of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers. Thus today’s Ohio Valley along West Virginia’s western boundary is a direct result of glacier impacts. Thick terraces of lake sediments still exist along the banks of the Monongahela River in the Morgantown-Fairmont area.

Unique plants and animals occur in high altitude muskeg bogs called glades by local residents, left over from the Ice Age climate. These areas, the largest of which include Cranberry Glades, Canaan Valley, and Cranesville Swamp, contain numerous plant and animal species not found elsewhere this far south.

The area composing West Virginia may be subdivided by its geologic and resultant physiographic characteristics into several different provinces. The easternmost of West Virginia’s geologic provinces is the Blue Ridge Mountains Province, which barely enters the state’s boundaries along the eastern margin of Jefferson County, near Harpers Ferry. The Blue Ridge Mountains are made of the oldest rocks exposed in West Virginia, which have, by and large, undergone chemical transformations due to intense heat and pressure associated with the upthrusting of the mountains. The degree of rock deformation is greatest near the source of the deforming force and diminishes away from that point. Thus, rock deformation is intensive in this easternmost part of the state, closer to the continental plate collision in the area of the present Atlantic Ocean, and is generally very mild in the western part.

The Ridge and Valley Province lies west of the Blue Ridge, and includes most of the Eastern Panhandle and adjoining areas to the southwest. Rock strata in this area, originally deposited as flat-lying beds of sediment, are strongly folded and sometimes broken by the compressional forces that came from the collision of continents. The steeply dipping orientation of the strata combined with differing susceptibility to erosion has produced the physiography of the Panhandle. Thick beds of erodible shales and limestones underlie broad valleys, separated by steep, sharp-crested, linear ridges held up by resistive sandstone layers. The Tuscarora Sandstone, a very hard, quartz-rich rock originally deposited as sand beaches along an ancient shoreline, is an especially prominent ridge former. Seneca Rocks and numerous other sheer rock cliff formations in the area are created by the erosion-resistant Tuscarora Sandstone.

Early settlers valued the agricultural promise of the broad valleys of the Ridge and Valley Province and moved into them in the mid-1700s. The prominent historic and current land use is agricultural, including livestock and poultry, grain crops, and orchards. Mineral resources include limestone, which is quarried for multiple purposes such as soil fertilization, construction aggregate, water treatment, coal mine dust suppression, and chemical uses.

West of the Ridge and Valley Province, the rock layers become relatively flat-lying, producing a very different terrain. Rather than the broad, linear valleys and parallel narrow ridges of the Ridge and Valley, topography to the west is generally less regular. However, there is a transitional area between the Ridge and Valley and Appalachian Plateau provinces that has been termed the High Plateau because it lies at generally higher elevations than the adjacent Ridge and Valley and Plateau areas. In the High Plateau, the rock strata are moderately folded and only rarely faulted (broken and moved), forming a transition between the intensely deformed strata to the east and the gently folded strata to the west. The eastern boundary of the High Plateau is very distinctly delineated from the Ridge and Valley Province by the escarpment of the Allegheny Front in the northeastern area of the state, and by the St. Clair Fault in the southeast.

The High Plateau encompasses the Potomac Highlands area, much of which lies within the Monongahela National Forest and is popular as a recreation area. Tourism and outdoor activities including hunting, fishing, canoeing, skiing, and cycling contribute to the economy. Historically, the High Plateau was timber country, and its culture incorporates a measure of colorful tradition from the timbering boom of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Timber continues to be an important product. There is also an important livestock raising tradition. Portions of the area are underlain by limestone which, combined with the relatively wetter and cooler climate of this part of the state, produces favorable conditions for grazing.

Most of West Virginia lies within the Plateau Province. Still, substantial differences in terrain, mineral resources, and land use occur within that area, and relate largely to differences in geology. The Plateau area contains mineral resources unmatched anywhere else in the eastern United States. West Virginia’s economy historically was founded on the rich coal deposits, extending from the Virginia and Kentucky borders in the south to the Pennsylvania and Maryland borders in the north. The Pittsburgh coal bed, which lies throughout a broad area of southwestern Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia, has been called the world’s single most valuable mineral deposit. It has been mined in West Virginia for well over 150 years, and continues to be a major producer today. The rugged southwestern coalfields contain numerous coal beds, including some of the highest quality anywhere in the world.

While the commercial coal deposits extend the length of the state from north to south, they disappear to the west, so that the westernmost counties have no coal production. Those areas are rich in natural gas and petroleum, however, and have a long history of development of those fuels. Natural salt brines contributed to the early economic development of parts of the state, most notably the Charleston-Kanawha Valley area, whose chemical industry originated from exploitation of the area’s shallow salt brines, beginning in the early 1800s.

Written by Ron Mullennex