| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

In his best-selling book, The Making of the President 1960, Theodore White said that West Virginia was among the most politically corrupt places in the country. The basis for White’s observation was the 1960 West Virginia Democratic primary election in which John F. Kennedy buried Hubert Humphrey by a mixture of state-of-the-art political techniques and old-style vote buying.

There is other evidence to justify White’s harsh assessment. In the last third of the 20th century, West Virginia governors were charged with felonies four times in federal court, with two acquittals and two guilty pleas. Two state senate presidents were convicted and sent to prison, and numerous elected and appointed officials (plus a few associates) suffered similar fates.

On February 14, 1968, a U.S. attorney announced the indictment of former Governor W. W. Barron (1961–65) and several close associates on public corruption charges. Although Barron was acquitted, all of his co-defendants were convicted. Suspicions were kindled when, soon after the trial concluded, the jury foreman visited a Charleston car dealer and bought a new luxury vehicle, paying cash. The foreman had been paid $25,000 to ‘‘hang’’ the jury but was able to produce an acquittal. He and Barron both subsequently pleaded guilty to jury tampering and were sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Their wives, who exchanged the money, were given immunity.

Following Barron in the prisoners’ dock was former Attorney General C. Donald Robertson Robertson. After pleading guilty in 1972 to charges involving kickbacks on federal housing assistance, Robertson served 14 months in prison.

Governor Arch Moore was indicted for extortion in 1975, near the end of his second term. He testified in his own behalf and was acquitted. Moore was elected to a third term in 1984. His second encounter with federal prosecutors came in 1990, after he was defeated in his bid for a fourth term. A Beckley businessman, John Kizer, claimed that Moore had exacted campaign contributions from him by promising favorable treatment with regard to his workers’ compensation account. Kizer had been repeatedly threatened with prosecution before he agreed to testify against Moore.

John Leaberry, a Huntington lawyer who had been Moore’s campaign director and later his workers’ compensation commissioner, called Moore and made arrangements to meet him near Parkersburg. Leaberry had recently appeared before a federal grand jury that was investigating Moore, and in contacting Moore he offered to discuss that testimony. Unfortunately for Moore, Leaberry was ‘‘wired’’ with a hidden microphone and the meeting was monitored by federal agents. Shortly afterward, Moore waived indictment and pleaded guilty. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

In 1993, West Virginia Lottery director Elton ‘‘Butch’’ Bryan and Ed Rebrook, counsel for the lottery, were convicted of insider trading and sent to prison. The gist of this offense was using privileged information in financial transactions. Bribery cases involved the 1989 prosecutions of former State Senate President Dan Tonkovich and Larry Tucker, his successor in the office.

Controversy and charges of corruption surrounded the West Virginia Supreme Court in the second decade of the 21st century, intensifying after the election of Allen Loughry as chief justice in 2017. Loughry, who previously had written a book on West Virginia political corruption, was charged in 2018 by the West Virginia Judicial Investigation Commission with violation of the state Code of Judicial Conduct and later indicted and convicted on criminal charges by a federal grand jury. In August 2018 the House of Delegates began impeachment proceedings against Loughry and the other sitting justices on the Supreme Court. Two justices resigned and another was censured before the replacement Supreme Court ruled that the impeachment articles violated separation of powers. Following the November election, three of the five justices on the court had been replaced by either gubernatorial appointment or popular vote. All three new justices were Republicans.

Some critics question whether West Virginia is any more corrupt than other places, pointing out that federal prosecutors have considerable leeway in pursuing cases. This is especially true with regard to those highly discretionary corruption cases that could be prosecuted in either federal or state courts or ignored altogether. The indictment of politicians, while guaranteed of high publicity, does not necessarily result in significant (or sometimes any) prison time.

For example, Michael Carey, who as U.S. attorney in Charleston sent Moore, Tonkovich, and Tucker to prison, published a list of public official prosecutions for 1984 through 1991 in the 1992 West Virginia Law Review. Of the 77 separate public official prosecutions listed by Carey, only a little more than one-third of the defendants were sentenced to any substantial prison time (from one to 20 years). By comparison, the official report of William Kolibash, who served as U.S. attorney in the Northern District of West Virginia at roughly the same time, deals exclusively with major drug traffickers and organized crime figures, all of whom received substantial sentences upon conviction. Carey, however, operated at the center of state politics and might be expected to encounter more political cases.

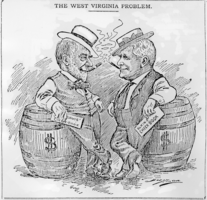

Nor should it be concluded that 20th century politicians were necessarily more corrupt than their predecessors. West Virginia politicians participated enthusiastically in the excesses of the late 19th century, routinely mixing business and politics. U.S. Sen. Johnson Newlon Camden (1881–87, 1893–95) exploited public office for personal gain, and a cartoon labeled ‘‘The West Virginia Problem’’ showed U.S. Senators Henry Gassaway Davis (1871–83) and Stephen B. Elkins (1895–1911) leaning on the pork barrel, checkbooks in hand.

Written by H. John Rogers