| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

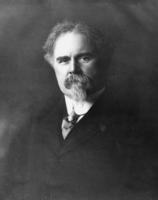

Governor William Alexander MacCorkle (May 7, 1857-September 24, 1930) was born in Rockbridge County, Virginia, on his father’s plantation in a rose brick house called Sunrise. West Virginia’s ninth governor, he was the last of six Democrats who held the office for a total of 26 consecutive years, the longest period of domination of the governorship by one party in our state’s history.

MacCorkle, the son of a Confederate major, promoted the development of the resources of West Virginia while worrying about the consequences of industrialization. He predicted in his inaugural address on March 4, 1893, that ‘‘the state is rapidly passing under the control of large foreign and non-resident landowners.’’ He asserted that ‘‘the men who are today purchasing the immense acres of the most valuable lands in the state are not citizens and have only purchased in order that they may carry to their distant homes in the North the usufruct of the lands of West Virginia.’’ He cautioned that the state shortly might be in a condition of vassalage to the North and East comparable to Ireland’s relationship to England.

MacCorkle was descended from the Scottish Highlands clan of Torquil or MacTorquil, which was modernized as MacCorkle. His father, also named William, had been a manager of the James River & Kanawha Canal. Both parents were of Scotch-Irish descent.

‘‘It was by pure luck that I came to West Virginia,’’ he wrote in his Recollections of Fifty Years of West Virginia. A traveler from Pocahontas County was passing the MacCorkle home in Virginia when his wagon broke down. Invited in for dinner, the West Virginian mentioned that he needed someone to teach school in the district of which he was a trustee. MacCorkle, then 19, went back to Pocahontas County with him. He spent about a year at Little Levels, which he later described as ‘‘one of the most beautiful sections of the earth.’’ He subsequently studied law at Washington and Lee University, graduating in 1879. He returned to West Virginia to practice law in Charleston. Initially, he taught school in the mornings and practiced law later in the day.

Later a rich man, MacCorkle lived modestly during his early years as a lawyer. ‘‘During the winter I slept on a bare table in a cold room,’’ he wrote, ‘‘with the thorough understanding with myself that I would some day surely sleep on a good bed in a warm room.’’ For awhile MacCorkle roomed with William E. Chilton, who became his long-time law partner and political associate. In 1881, he married Belle Goshorn, the daughter of an established Charleston family. There were two children, William G. and Isabelle. Elected Kanawha County prosecuting attorney in 1880, MacCorkle served until 1889.

MacCorkle was the Democratic Party nominee for governor in 1892. He defeated Republican Thomas E. Davis of Ritchie County by less than 4,000 votes. His election as governor represented the triumph of the so-called Kanawha Ring, led by MacCorkle, Chilton, and U.S. Sen. John Kenna. Unable to enact his own party’s programs after the election of a Republican legislature in 1894, MacCorkle cooperated with the opposition in efforts to raise the standards of state institutions and to free those agencies from the influences of politics.

Like many other West Virginia governors, MacCorkle was concerned about highways. He foresaw the need for consolidating the county road systems under a state agency. During his administration, MacCorkle borrowed money on his personal credit to complete the copying of land titles recorded in the Virginia Land Office in Richmond. He urged that the West Virginia Board of Health control the examination of physicians wanting to practice medicine in the state; proposed that banks be required to keep on hand at least 15 percent of deposits; and recommended investigation of insurance companies desiring to do business in West Virginia.

MacCorkle was the last of the so-called Bourbon governors, Southern-leaning Democrats who clung to traditions of the agrarian past while entering into uneasy compromise with the emerging industrial order. The Republicans who followed were whole heartedly committed to the new age. Republicans took control of the legislature midway through MacCorkle’s term, and his collaboration with them marked a transition from one political era to the next.

At the end of his term as governor, MacCorkle resumed the practice of law in Charleston. Many of his efforts were devoted to the industrial development of the Kanawha Valley. The period saw the building of railways, interurban rail lines, coal operations, and manufacturing enterprises. The Kanawha Land Company, formed under his leadership, attracted two glass companies. The South Charleston Crusher Company, formed by MacCorkle and others, produced about 500 tons of stone ballast a day for the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. MacCorkle later served a term in the state senate. He was elected to that position in 1910.

He was an organizer of the Citizens National Bank, absorbed in 1929 by the Charleston National Bank, which he served as chairman. In World War I, MacCorkle was state chairman of the Liberty Loan campaigns. He was the author of Some Southern Questions, The Personal Genesis of the Monroe Doctrine, and The Book of the White Sulphur, as well as the autobiographical Recollections of Fifty Years of West Virginia. He lived in the South Hills section, overlooking the Kanawha River and midtown Charleston. His handsome mansion, later a museum, was named Sunrise for his ancestral Virginia home. It remains a Charleston landmark.

Gov. William A. MacCorkle died of pneumonia. He was cremated, and the ashes were sealed in a bronze urn and placed in a shrine on the estate.

Read Gov. MacCorkle’s inaugural address.

Written by Glade Little

Morgan, John G. West Virginia Governors, 1863-1980. Charleston: Charleston Newspapers, 1980.

MacCorkle, William A. The Recollections of Fifty Years of West Virginia. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1928.