| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

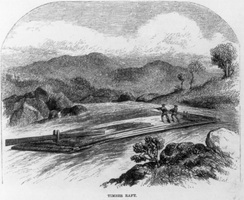

The most colorful era of the lumber industry in West Virginia occurred in the days when loggers floated their timber downstream to the mills. During the summer and fall, woodsmen labored from daylight until dark, six days a week, felling, trimming, and skidding timber. Cutting and skidding continued during the winter when ice facilitated the quick passage of logs down the mountain to the river landing below. ‘‘Arks’’ from 70 to 100 feet long and 18 feet wide were built. The bunkhouse ark contained double-decked bunks and a large stove to keep the men warm; the cooking and dining hall occupied a second ark.

The main drive down the river began with the first sign of spring when the ice began to break up. The logs were then rolled into the swollen stream and carried along by the current, with the arks following behind. Log driving was demanding, dangerous work, much of it performed in icy water. Many West Virginia rivers could not be successfully driven because they were too rapid, narrow, or filled with obstructions, but others were ideally suited for driving. The Greenbrier became the most famous of the driving rivers, its reputation mythologized in the popular novels of W. E. Blackhurst and the poetry of Louise McNeill.

Loggers who worked along navigable streams preferred to construct log rafts to float their timber downstream, rather than driving loose logs. The average log rafts consisted of about 70 logs. The earliest rafts generally were assembled by fastening the logs together with poles running across the timbers and held together with wooden pins. Nails and chain dogs, two wedges joined by a chain, made the raft strong and gave it flexibility and yet allowed it to be constructed and dismantled quickly. To the rear of the raft were attached oars from 20 to 50 feet long which permitted rafts men to steer.

The history of rafting is as varied as the rivers themselves. At Rowlesburg, Preston County, a lumber depot built at the junction of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Cheat River served as a destination of many rafts steered down the Cheat River. The Kanawha River was, of course, the drainage stem of several important interior rivers, and large sawmills along its banks were the destination of innumerable rafts in the 19th century. Log driving and rafting peaked prior to 1900 when railroads replaced streams as the chief means of transporting logs to the milling centers.

Written by Ronald L. Lewis

Clarkson, Roy B. Tumult on the Mountains: Lumbering in West Virginia 1770-1920. Parsons: McClain, 1964.

Lewis, Ronald L. Transforming the Appalachian Countryside. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Blackhurst, W. E. Riders of the Flood. Parsons: McClain, 1954.