| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

| Back to e-WV

| Back to e-WV

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

The West Virginia Encyclopedia

There are 424 recorded prehistoric mounds in West Virginia, left by ancient people who once occupied the region. Most are constructed of earth or stone or a combination of both. The majority of mounds in the state are concentrated along the major river valleys, including the Kanawha, Ohio, and Potomac. Major mound groups cluster near South Charleston, Moundsville, and Moorefield. A significant number of rock mounds are found along ridgetops in Nicholas County. The largest earthen, conical mound in North America is the Grave Creek Mound, located in Moundsville.

Archeologists divide prehistory in the eastern United States into several cultural periods. The majority of mounds identified in West Virginia were constructed during the Early Woodland Period (1000—200 B.C.), primarily in the period referred to as Adena (500 B.C.— A.D. 200). Because much archeological data in Appalachia is still elusive, little is known of everyday Adena life. What we know comes largely from the mounds and earthworks they left behind. The Adena were hunters and gatherers. They built mounds over the remains of chiefs, shamans, or other people of high social standing. The remains of the common folk were burned and buried in small log tombs. The Adena lived in circular houses made of wickerwork and bark.

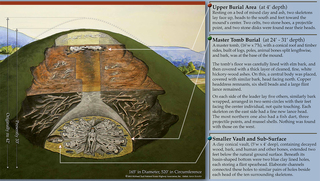

Adena mounds were generally constructed in stages. Excavations conducted at Cotiga Mound in Mingo County identified at least six stages of mound construction. Circular, paired-post structures are often found underneath mounds. Some archeologists believe that these sub-mound structures were charnel houses used in burial rituals; others suggest that they were roofless ritual enclosures not necessarily used for mortuary activities. Grave goods from Adena Period mounds include hematite celts and cones, copper beads and bracelets, tubular pipes, inscribed tablets, and shell beads.

During the 19th century, the Myth of the Moundbuilders was a popular notion. It was thought that a lost race or civilization, such as the Lost Tribes of Israel, had built mounds in North America. Many people believed that American Indians were savage and primitive, and would have been incapable of constructing large earthworks. Another belief was that the mound builders were giants; inaccurate field measurements of some Adena skeletons revealed unusually tall and powerful men and women over seven feet tall.

Some of the earliest studies conducted in North American archeology centered on mounds. In 1846, Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis conducted a survey of mounds found in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, including Western Virginia. Their work culminated in the 1848 publication, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. While their study was a landmark, it supported and perpetuated the Moundbuilders Myth.

In 1882, the Smithsonian Institution established the Division of Mound Studies. Cyrus Thomas, appointed to direct the division, sent teams of archeologists to explore and excavate mounds in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. One was the South Charleston Mound in Kanawha County. Excavations identified a skeleton in a log tomb 24 feet below the mound summit, laid on sheets of copper and surrounded by 10 other burials. In 1894, Thomas published the Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. This report, supported with scientific evidence, concluded that the mounds were built by the ancestors of Native Americans, finally putting the Myth of the Moundbuilders to rest.

Written by Patrick D. Trader

McMichael, Edward V. Introduction to West Virginia Archeology. Morgantown: West Virginia Geological & Economic Survey, 1968.

Norona, Delf. Moundsville's Mammoth Mound. Moundsville: West Virginia Archeological Society, 1954, Reprint, West Virginia Archeological Society, 1998.